You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Superman Returns Official Superman Returns Discussion

- Thread starter Wheels

- Start date

Drizzle

Here for the food

- Joined

- Apr 16, 2007

- Messages

- 39,415

- Reaction score

- 44,800

- Points

- 118

I won’t lie, this still gives me a jolt of nostalgia:

I still consider this to be one of the best teasers for a CBM. Of course the Williams music and Brando voiceover go a long way but I remember being excited as hell seeing this for the first time.

elgaz

Sidekick

- Joined

- May 11, 2005

- Messages

- 4,676

- Reaction score

- 1,201

- Points

- 103

Posted here on page 2 about 12 years ago and unfortunately my thoughts are pretty much still the same about this movie, despite the odd rewatch. I don't hate the film, but it's a flawed one and I do question a lot of the choices Singer made with regards to the storyline, trying to continue Donner's universe, and even casting in some cases.

One thing that has changed is that I probably appreciate Brandon Routh a bit more now. Coming off Superman Returns, I hadn't really seen him in anything else but with the passage of time (and his return to the role in CW's Crisis episodes), I've cut him a bit more slack. He was good in the role but I do feel he was somewhat hampered by the more melancholic characterization Singer created for the story.

One thing that has changed is that I probably appreciate Brandon Routh a bit more now. Coming off Superman Returns, I hadn't really seen him in anything else but with the passage of time (and his return to the role in CW's Crisis episodes), I've cut him a bit more slack. He was good in the role but I do feel he was somewhat hampered by the more melancholic characterization Singer created for the story.

Mandon Knight

We did it......

- Joined

- May 1, 2014

- Messages

- 15,934

- Reaction score

- 5,363

- Points

- 103

I think if viewed as a late 30's / early 40's presentation of the character and stylings, it works to a degree, its flawed in so many ways, across a number of points but having not seen it for a good few years, I will always 'defend it' in the sense that for me, the good outweighs the bad.

Boswell is terrible and the character choices made by Superman are poor, BUT, Routh is imperious (for me) as both Clark & Superman.

I need to re-watch this.

Boswell is terrible and the character choices made by Superman are poor, BUT, Routh is imperious (for me) as both Clark & Superman.

I need to re-watch this.

Sawyer

17 and AFRAID of Sabrina Carpenter

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2004

- Messages

- 114,438

- Reaction score

- 27,912

- Points

- 203

Just rewatched for the first time in awhile, and I can’t promise that this isn’t just a reflex against the dourness of Snyder, but my opinion of SR has actually improved quite a bit.

Hardly perfect, but there was some real heart to this thing.

That being said, Bosworth was miscast (though still largely fine) and both she and Routh were too young for the story being told. And unfortunately, the sex pest did actually make a damn good Lex.

Hardly perfect, but there was some real heart to this thing.

That being said, Bosworth was miscast (though still largely fine) and both she and Routh were too young for the story being told. And unfortunately, the sex pest did actually make a damn good Lex.

Primal Slayer

How lucky are WW fans?

- Joined

- Jun 30, 2005

- Messages

- 28,785

- Reaction score

- 7,016

- Points

- 103

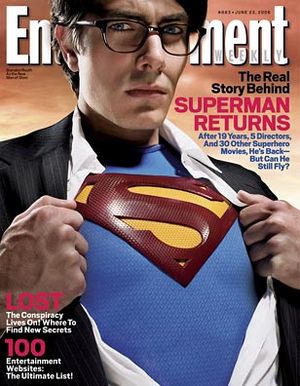

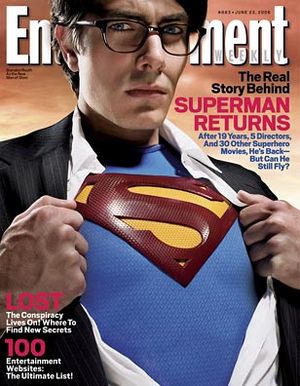

If anyone wants to "relive" the magic of meeting Routh and the story behind it all

His eyes are Bambi brown, not Superman blue. In the face, he seems more Superboy than Man of Steel, even though at 26, Brandon Routh is the same age Christopher Reeve was when the late actor assumed the mythic mantle almost 30 years ago. But these are quibbles. As he stands on the set of Superman Returns, filling out his unforgiving body sock with supreme self-confidence, Routh at least looks the part, especially after he puts his tinted contacts in. Now it's time to see if he can fly. We mean this literally: Routh is about to go up, up, and away into the rafters of Fox Studios in Sydney, Australia. We're inside one of the many cavernous warehouses occupied by the production, on the rooftop set of the Daily Planet, Metropolis' biggest newspaper and the employer of both Clark Kent (Superman's bumbling alter ego) and spelling-challenged ace reporter Lois Lane (Bosworth). Filming is under way on an emotionally charged moment: Superman's reunion with Lane, his former flame, after a five-year absence spent searching for his homeworld of Krypton. Alas, Lois has moved on. She's engaged to Richard White (James Marsden), nephew of Planet editor Perry White (Frank Langella). She even has a son. A son who's around 5 years old. Hmmm...

They conclude their awkward rendezvous. Say their goodbyes. And with that, a crew member pushes a button and a computerized rigging system tugs on the harness under Routh's suit, hoisting him into the air. His curly forelock flutters in the breeze. Routh smiles. He keeps ramrod-perfect form, all the way to the rafters. Then he descends, his cape spreading above him like an unfurled flag.

But it's not good enough for director Bryan Singer. Sitting behind a bank of monitors, the famously demanding helmer of the first two X-Men films doesn't like the way Routh's arms look during flight. He wants to see him do it again, this time with two arms in front, hands fisted.

And again, this time bringing one arm up.

And again. And again. And — TWANGGGGGGGG!

''What was that?'' asks Singer.

That was the sound of Routh hitting a rafter.

There's a hush. Everyone looks up in the sky to see if the franchise is falling.

Routh is brought down — he's fine. ''I guess everyone thought I was unconscious because I didn't say anything,'' Routh recalls later. ''But I didn't say anything because Kate was down below, and the camera was shooting her. I didn't want to disturb her.''

Aw, shucks. What a sweetie! Polite. Selfless. Noble. Exactly the kind of guy you expect Superman to be. Exactly the kind of guy Superman has always been since his debut in Action Comics No. 1 in 1938, the proverbial Big Bang of superhero fiction. And exactly the kind of guy everyone thinks of as...a big bore. Take it from Routh himself: ''People say that Superman is unrelatable. A Boy Scout. White bread. Just a dumb comic-book character.'' Here on the verge of good ol' Superman's splashy reentry into mainstream pop culture, the risky $363 million question for Superman Returns (out June 28) is this: Can anyone still believe in good ol' Superman anymore?

The answer is no. Or at least it was. Ever since 1993, when Warner Bros. (a division of EW parent Time Warner) reacquired Superman's film rights from producer Alexander Salkind, the studio seemed to think that the Man of Steel needed a modern makeover. Perhaps it was all the bizarre little bits that had never been credibly explained. How can he fly? How come no one sees through the Clark Kent disguise? How can he be so gosh-darn good? J.J. Abrams, the Mission: Impossible III writer-director who once tried his hand at making Superman relevant, suggests that the Christopher Reeve versions got a free pass on these questions. ''Superman was the movie that told us, 'You will believe a man can fly.' It did, and we bought everything that came with it,'' he says. ''Now you see flying men everywhere. Movies, TV, commercials. Even The Matrix, which in many ways was Superman reinvented. You can't just win on spectacle anymore. You have to dig deeper.''

And, it seems, go darker. Since the implosion of the Superman franchise in 1987 with Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, the superhero marketplace has grown grim and more psychologically complex, if sometimes cheaply so. Tim Burton's 1989 movie Batman epitomized the new heroic modality — a dark knight for an edgy, grungy, cynical new generation. Even DC Comics had turned against the Man of Tomorrow in 1992 by killing him off at the hands of a homicidal alien named Doomsday. (They quickly resurrected him, of course.) The gimmick sold like gangbusters. In fact, it was Warner's original intention to use that story line as the springboard to revive the franchise. Fittingly, the studio turned to Burton himself to handle the revamp. The demolition and reconstruction of Superman was on.

But it never took flight. Not with Burton. Nor with directors Brett Ratner or McG, who separately tried to bring to screen a script by Abrams. Each learned the hard way what comic-book readers have known for decades: Superman isn't obsolete. He's timeless and, perhaps, unchangeable. Still, by the summer of 2004, after 11 years and over $65 million in development costs, it seemed as if Superman would never be reborn. ''The smart thing would have been to let everything cool down, and spend some time figuring out what to do next,'' says Jeff Robinov, Warner Bros.' president of production. ''But then we heard Bryan's pitch, and we were finally in business.''

Bryan Singer is pretty old-fashioned when it comes to his superhero spandex. He wasn't even familiar with the modern comic world's reigning superstars, the X-Men, until he was pitched that film and latched onto them as an allegory for feeling freakish in a freak-hating world. He doesn't consider himself a ''comic-book guy.'' But he loves Superman. Believes in him. As a kid, he got hooked on the 1950s George Reeves TV series, and then fell hard for director Richard Donner's Superman and its cheery fantasy about the ultimate stranger in a strange land. ''I'm adopted. I'm an only child. And I have blue eyes,'' says Singer. ''When I first saw Superman and his blue eyes, I felt a very strong identification.'' Naturally, he decided to become a movie director.

Singer is also gay, a fact that he doesn't really like to talk about in the press. He admits that his sexual identity is relevant to his work, especially the outsider-themed X-Men movies. But he resists a similar reading of his current project. ''Interestingly enough,'' says Singer, ''Superman Returns is the most heterosexual movie I've ever made.''

The director has been dreaming of his own Superman project for years, though his take differed dramatically from the pitches Warner Bros. had been developing. Singer wanted to make a Superman firmly grounded in its popular history, one set in the wake of Superman II, in which the Man of Steel fought disco-suited bad guys and got busy with Lois Lane in the Fortress of Solitude. Singer wanted to use parts of John Williams' 1978 score. He wanted to use parts of Marlon Brando's performance as Superman's Kryptonian father. And, dammit, he wanted every stitch of those outrageous tights. ''Superman has a blue suit, a red cape, and an S on his chest. These are undeniable facts,'' says Singer. ''If you're going to make Superman, make Superman. Don't be afraid of it.''

Warner Bros. was well aware of Singer's Super-dreams as the McG-Abrams project was turning into a nightmare in June 2004. The studio had been developing a remake of the sci-fi flick Logan's Run with Singer, and according to Robinov, ''the subject of Superman had come up.'' As Singer was preparing to leave for Hawaii for a short vacation with his X2/Logan's Run writers Dan Harris and Michael Dougherty, Warner Bros. asked him to pitch his idea formally. The Hawaiian holiday became the first production meeting of Superman Returns. The trio envisioned a rich, romantic, biblical-feeling epic. Their plot would have a typically over-the-top Lex Luthor real estate swindle — this time, using the mysteriously powerful crystals in Superman's Fortress of Solitude to engineer the deadliest landgrab known to man. (Singer and the writers decided on the plane to pursue Kevin Spacey and Parker Posey for their villains.)

But beyond comic-book high jinks, Singer and the scribes decided they would emphasize the Man of Steel's alienation, the Superman-Lois-Richard love triangle, and the tacit mystery surrounding the paternity of Lois' son. And it would all pivot on the vaguely self-aware where did Superman go? conceit, which not only devastates Lois but spurs her to write an article called ''Why the World Doesn't Need Superman.'' ''The idea,'' says Dougherty, ''was to address the perceived irrelevancy of Superman by making a movie about the theme of his irrelevancy.''

Singer's vision would also put the franchise in line with the Superman of DC Comics and the Clark Kent of Smallville, a clever cash cow from Warner Bros. TV that kept the brand in the mainstream consciousness. Moving from revisionism to retro faster than a speeding bullet, Warner Bros. bought the pitch. Interestingly, the decision immediately followed the studio's embarrassing movie revamp of Catwoman.

Meanwhile, Brandon Routh was growing impatient. The Iowa native had come to Hollywood with big acting ambitions, but by 2004 all he had to show for it was a year on a soap opera, a couple of TV appearances, and a cute girlfriend that he met at the bowling alley where he worked as a bartender. All his life, Routh had been told he looked like Christopher Reeve, and he had been hoping the resemblance might get him his big break: The actor was one of five finalists for McG's Superman. When the director left the project, Routh was told nothing. Now he was trolling Internet sites for intel on what Singer was up to. ''I knew he had my audition tape. I kept wondering, Is he going to call?'' says Routh. ''It was like it had all faded away. I was feeling very unsatisfied.''

On the morning of Aug. 13, 2004, the actor got the call. Singer wanted a meeting ASAP. Routh's reaction was exasperated relief: ''Finally! I mean, I thought I had done pretty good.''

Singer met Routh for coffee that day and left knowing he had his star. He also had a commitment from Spacey to play Lex, provided the actor could get time off from acting in The Philadelphia Story at England's Old Vic Theatre, where he's the artistic director.

It was a nice start to an intensely hectic fall. Having lucked out in finding a replacement so quickly for McG, Warner Bros. was now pushing Singer to stay on McG's schedule toward a June 2006 release. Singer began scouting in Australia, vetting the script, designing the suit, and casting. He admits that he was partly looking for youth in his two leads so they could age well into sequels. But 23-year-old Bosworth (Blue Crush) was plenty old enough to connect with Lois' heartbreak and anger over the disappearance of Superman. Prior to shooting, the actress reportedly broke up with beau Orlando Bloom. So, ''if you [get] a strong feeling of that, it's probably because it was an interesting time in my life,'' she says.

Warner Bros. eventually greenlit Superman Returns at $184.5 million, though not until after what Singer calls a ''terrible, terrible night'' of budget slashing that included nixing a full-scale, $20 million-plus downtown Metropolis set that would later have become part of an Australian theme park. Digital effects would create cityscapes or extend the sets. However, the cornfield is real: To create the Kent family farm, the production planted its own crops. ''That corn cost $50 an ear to grow,'' says film legend Eva Marie Saint, who plays Clark's beloved Ma Kent, and who insists she isn't joking. ''That's just one tiny story about why this movie cost so much.''

Other major expenses included complex effects sequences like the one in which Superman saves a plane from crashing into a baseball stadium — a constantly evolving set piece that was shot and reshot throughout production, according to Routh. Complications with the greenscreen work reached a crisis late in production during the shooting of the film's apocalyptic climax inside three massive water tanks. Singer wasn't certain what he needed; the cast and the crew were exhausted and confused. The producers asked the studio for a three-week recess to edit their footage and reassess budget. ''I was all for that break. The water was a nightmare,'' says Bosworth. ''Every day I was like, What the hell are we doing?''

Ultimately, extra effects and the addition of a bank-robbery sequence — which gained the movie a trailer-friendly bulletproof-eyeball moment — pushed the budget over $200 million. According to the studio, Superman Returns' price tag is $204 million. Without the Australian tax credits: about $223 million. Add in the bills for Ratner and McG, which will count against Singer's film, and the total comes to an estimated $263 million, plus potentially another $100 million in worldwide marketing costs. As shooting wrapped last fall, Warner Bros. inked a deal to split Superman's production budget with an independent film company that will share in the revenue.

But it's superexpensive, nonetheless. By most reckonings, Superman Returns will likely need to gross over $600 million worldwide to make its money back, a feat only two superhero adaptations have ever accomplished: Spider-Man and Spider-Man 2. Superman Returns is further challenged by a 2-hour, 37-minute running time. Robinov, however, is hoping audiences will embrace the film as the Titanic of superhero movies, and the cast is feeling confident. Says Marsden, ''If somebody gave you $200 million to make a movie that could reach the most people you could — who would it be about? The answer is either going to be Superman or Jesus.''

The larger question remains: In an era of the vengeance-driven Batman Begins, how relevant is a values-driven Superman Returns? Early versions of the script included nods to a post-9/11 world, but Singer and his writers chose to cut them, feeling it was too much too soon for Superman to address. Still, they do present their hero as a citizen of the world, not just an avatar of ''truth, justice, and the American way.'' Singer, who has two more Superman films in mind, believes that the character's cool lies in his universality. ''Is Superman relevant?'' he asks. ''Look around. Aren't we crying out for him?''

Speaking of second comings, Brandon Routh is waiting again. Waiting for the inevitable Christopher Reeve comparisons. Waiting for the chance to prove he can do more than just be Superman (''I have every intention of being an accomplished actor in many other films,'' he says). And waiting for everything to change. ''I already know I can't go to the grocery store. Even if only a few million people saw the movie, that would still be a problem,'' he says. ''But a few billion seeing it wouldn't be bad, either.'' Ah, Superman. Ever the idealist.

Greatest American Hero? | EW.com

His eyes are Bambi brown, not Superman blue. In the face, he seems more Superboy than Man of Steel, even though at 26, Brandon Routh…web.archive.org

Similar threads

Superman Returns

Superman Returns Prequel comics question?

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 3K

Superman Returns

Superman Returns - Free Downloads On The XBOX 360 Live Marketplace

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 1K

Superman Returns

Superman Returns tv spots in HD

- Replies

- 34

- Views

- 3K

Superman Returns

WB Releases Superman Returns Production Notes!!

- Replies

- 25

- Views

- 4K

Superman Returns

Superman Returns with FIREWALL DVD

- Replies

- 9

- Views

- 2K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)

Staff online

-

SwordOfMorningSuper Moderator

-

DKDetectiveElementary, Dear Robin (he/him)

-

Lily Adler🎄 Peppermint Mocha 🍫

Latest posts

-

-

🌎 Discussion: Criminal Justice, Prison Reform, Police Reform, and Other Criminal Justice Issues (4 Viewers)

- Latest: squeekness

-

-

-