Thundercrack85

Avenger

- Joined

- Sep 2, 2009

- Messages

- 21,668

- Reaction score

- 8

- Points

- 33

Obama's cronyism is something that really should be reported on more.

Cable companies are rattled over public demand for net neutrality. But VICE believes that they've got it so bad that they're funding consumer groups to rally against a democratic internet.

The site believes that cable companies are funding astroturfing campaigns across the U.S. to parrot their views. It points to Broadband for America, for instance, which claims to be a coalition of independent advocacy groups, but is in fact funded by the NCTAthe lobbyist organisation for big cable. Then there's the American Consumer Institute, an anti-net neutrality group which receives the majority of its funding from the CTIAwhich represents the American wireless industry.

It's not illegal to donate money to consumer groups. It's not illegal for consumer groups to speak out against net neutrality. But when you have to pay people to get your point heard, it's difficult to believe that much good can come to the wider world as a result of your beliefs. Remember, you can still tell the FCC what you think about its plans to reform broadband.

The public wants net neutrality. We've all made it pretty clear. But the cable companies don't. They've already ginned up some lobbyist-funded, anti-neutrality groups, but now it seems they're going a step further, tricking real groups into joining up.

According to reports by VICE, a few real advocacy groups manned by real people with real interestsmany of which have little or nothing to do with the telecomm industry have been conned into supporting Broadband for America one of the anti-neutrality advocates funded almost entirely by cable lobby money.

Some of the groups listed as supporters, like the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals, said they supported the expansion of broadband to rural and underserved areas, but weren't made aware of Broadband for America's net neutrality stance. Other groups, like the Ohio League of Conservation Voters, said they didn't even know they'd be listed as allies.

The executive director of the Ohio League of Conservation Voters even went so far as to put out a message to Broadband for America.

From VICE:

The Ohio League of Conservation Voters does not endorse your position on broadband. This is not a policy area that we take positions on. Why are we listed as a Broadband for America member? I am unaware of Ohio LCV taking any position on broadband issues and I have been Executive Director since 2011. The Ohio LCV is not a member of Broadband for America. Remove us from your listing of members.

If we want to save net neutrality, there is a long, arduous fight ahead, and it looks like the cable industry and the FCC are content to play a little dirty. But it doesn't change the fact that everyone with a brain still wants net neutrality.

This week, Columbia law professor Tim Wu announced that he's running for lieutenant governor of New York. Wu is the guy who invented the term net neutrality. And regardless of which state you call home, this is exciting news.

Wu is a lot like you and me. He doesn't want to allow fast lanes on the internet. He doesn't like how big telecom companies take advantage of the American people. He does want to block the Comcast-Time Warner Cable merger. And as New York's lieutenant governor, he actually could, since Time Warner Cable has substantial business operations in the state.

The campaign won't be easy. Along with his running mate, Fordham law professor Zephyr Teachout, who's running for governor, Wu is challenging incumbent Andrew Cuomo and his choice for lieutenant governor, Kathy Hochul. Teachout and Wu say they're going to take a more progressive approach and point out how Cuomo's been leaning too far to right lately. It certainly helps their cause that one of the hottest issues in the news this summernet neutrality, of courseis one that Wu's famous for spearheading. He did invent the phrase, after all.

We'll be watching Wu as he takes his forward-thinking views on the internet to the floor of the political arena. Again, it's going to be a tough fight. Wu's doing it for all the right reasons, though. "You can expect a progressive-style, trust-busting kind of campaign out of me," he recently told the Washington Post. "And I fully intend to bridge that gap between the kind of typical issues in electoral politics and questions involving private power."

Sounds good, Tim! If you're eager to hear more about Wu's leanings, he'll be testifying before Congress about net neutrality on Friday.

This weekend at the U.S. Conference of Mayors annual meeting in Dallas, some mayors will take a strong stand in support of net neutrality. According to an op-ed by Mayors Ed Lee of San Francisco and Ed Murray of Seattle, the city leaders are unveiling a resolution calling on the FCC to preserve an open Internet.

This is good and welcomed news. The mayors get it: a free and open Internet is critically important for the health of U.S. cities. "The Internet has thrived because of its openness and equality of access," reads the mayors' op-ed. "It has spurred great innovation, while providing a level playing field for its users. It allows everyone the same chance to interact, to participate, to compete."

Here's some even better news: while the FCC may have a role to play in promoting and protecting a neutral Internet, city governments don't have to rely entirely on the FCC. In fact, there are two things Mayor Lee can do right now to protect the future of our open Internet: strongly support municipal wireless and light up the dark fiber that weaves its way under the city of San Francisco. And other mayors around the country have the same opportunity, if they've got the will to take it.

Light up the Dark Fiber

"Dark fiber" refers to unused fiber optic lines already laid in cities around the country, intended to provide high speed, affordable Internet access to residents. In San Francisco alone, more than 110 miles of fiber optic cable run under the city. Only a fraction of that fiber network is being used.

And San Francisco isn't alone. Cities across the country have invested in laying fiber to connect nonprofits, schools, and government offices with high-speed Internet.

Light Up Competition

Community broadband is not a silver bullet for net neutrality. But it can help promote competition by doing one essential thing: offering people real alternatives.

In most U.S. cities there is only one option for high-speed broadband access. This is because in the early 2000s the FCC thought that competition alone would do the job of regulatory oversight, but instead Internet access providers consolidated to the point of no competition. And this lack of competition means that users can't vote with their feet when monopoly providers like Comcast or Verizon discriminate among Internet users in harmful ways. On the flipside, a lack of competition leaves these large Internet providers with little incentive to offer better service.

A non-neutral Internet, enabled by access monopolies, means that new businesses in cities could be crippled from reaching potential customers, as users are channeled toward incumbent websites and those in a special relationship with the Internet access providers. The result: a less diverse Internet and a weaker local economy.

Real Political Will Can Overcome Artificial Political and Legal Barriers

Let's take a look at Chattanooga, Tennessee, a city that has better broadband than San Francisco. Chattanooga is home to one of the nation's least expensive, most robust municipally owned broadband networks. The city decided to build a high-speed networkinitially to meet the needs of the city's electric company that needed a way to monitor new equipment being installed throughout Chatanooga. Then, the local government learned that the cable companies would not be upgrading their Internet service fast enough to meet the city's needs. So the electric utility also became an ISP, and the residents of Chattanooga now have access to a gigabit (1,000 megabits) per second Internet connection. That's far ahead of the average US connection speed, which typically clocks in at 9.8 megabits per second.

And in Missouri, the city of Springfield crafted laws to navigate around state restrictions on municipal broadband. Now Springfield provides its own access service, SpringNet, and is offering residents high capacity fiber Internet service.

Unfortunately, many cities have faced serious barriers to their efforts to light up dark fiber or extend existing networks.Take Washington D.C., where the city's fiber is bound up in a non-compete contract with Comcast, keeping the network from serving businesses and residents.

San Francisco doesn't have the same kind of contractual barriers that D.C. has, but the city's network is still under-used. San Francisco's fiber connects important institutions like libraries, schools, public housing, and public wi-fi projects. However, according to Harvard University researcher Susan Crawford, San Francisco "has not yet cracked the nut of alternative community residential or business fiber access."

Here, too, San Francisco is not alone. Right now 89 U.S. cities provide residents with high-speed home Internet. And dozens of cities across the country have the infrastructure, such as dark fiber, to either offer high-speed broadband Internet to residents or lease out the fiber to new Internet access providers to bring more competition to the marketplace. So the infrastructure to provide municipal alternatives is there in many places we just need the will and savvy to make it a reality that works.

That said, the most outrageous barrier is a legal one: state laws, promoted by powerful incumbent Internet access providers, that impede competition by imposing restrictions on cities' ability to grow broadband networks. Twenty states currently have laws that restrict or discourage municipalities and communities from building their own broadband networks.

Fortunately, the FCC has said it will challenge these laws. But the FCC can't create the political commitment to actually making community broadband happen. That's up to us.

All hands on deck

It's going to take a constellation of solutions to keep our Internet open. But where those options don't depend on regulators and legislators in D.C., we don't need to wait.

Whether it's lighting up dark fiber or starting a municipal broadband network, we can tell our elected officials that it's time to take action to protect our open Internet.

That's why we're calling for all hands on deck. In cities with dark fiber, like San Francisco, it's time to light it up. Mayor Ed Lee knows the importance of an open and free Internet. San Francisco is renowned for being home to some of the most innovative Internet companies and startups in the world. The city should be a leader in community broadband as well.

But what's really exciting is that this is one area where we call all be leaders. We can all organize locally and urge our city officials to support municipal and community broadband projects. To help spur that work, EFF will be sharing more ideas and tools for activism in the coming weeks.

And remember: the FCC is seeking public comment about how to craft new network neutrality rules. Visit DearFCC.org right now and make sure the agency hears us loud and clear: we're not going to let a few Internet access providers decide the future of our open Internet.

Pending public rage, the FCC's flawed net neutrality rules will kick in later this summer. And yet, despite the impassioned coverage in the media, it's obvious that most people are still missing the point. As Wired points out today, a type of internet fast lane already exists, and nobody's talking about how to shut them down.

Fast lanes don't require slow lanes

There are actually two different types of internet fast lanes. The one you're used to hearing about involves paid prioritization, or, the practice of companies paying internet service providers (ISPs) for preferential treatment. These fast lanes actually work like toll booths, where paying companies get to go through the gate first when traffic is congested. It's a bad idea, and one that the new FCC rules would allow.

The other type of fast lane, though, already exists. It's been happening for years, and the new FCC rules don't even address it. As Wired explains in the first of a three-part series on net neutrality, plenty of large companies like Netflix and Google already enjoy the benefits of a type of fast lane that's created when they pay for the ability to connect directly to ISPs like Comcast and Verizon through special "peering connections" or "content delivery services."

Peering connections and content delivery services are two different ways of solving the same problem. When a company's traffic gets big enough, it's going to start clogging the regular pipes that carry traffic from the company's servers to the ISP. This is commonly known as the internet backbone.

Think of it like the interstate that connects two cities. An obvious way around this congestion is simply to build a new highway that connects the servers to the ISP directly. This is known as a peering connection. Alternatively, a company can ensure even faster connections by building servers inside the ISP, establishing a content delivery service. The FCC's current rules don't address this type of fast lane at all, and according to Chairman Wheeler, the agency isn't interested in addressing them any time soon, either.

But that doesn't make these fast lanes harmless

This second kind of fast lane is how Netflix has improved streaming quality for customers on Comcast and Verizon's networksalbeit at a cost to consumersin recently months. They're not paying the ISPs to prioritize traffic, per se. They're actually paying for new infrastructure that only they can use. Google was the first company to set up these kinds of agreements with ISPs, and now it's pretty common with all the major players, from Apple to Facebook. Everyone benefits, because customers enjoy faster connections to sites they visit frequently without slowing down connections for others. That's why peering agreements don't get the same negative hype; they don't come with the same consequences as the types of prioritization the FCC would allow.

Of course, that doesn't mean that the internet's existing fast lanes are necessarily a good thing. These arrangements have traditionally been made without money exchanging hands and for the benefit of the consumer, but it's easy to see it's all starting to go wrong. Now that Netflix is brokering high dollar deals for peering, you can imagine how competing video services (i.e. the ones that can't afford to write big checks to Comcast) are at a disadvantage. Even though the fast lane applies to a different part of the internet's infrastructure, it's still a fast lane that compromises the extent to which the internet is free and open.

So what can we do about it?

That's a tough question. On one hand, the internet's been working pretty well so far without much oversight from the FCC or anybody else. Those Netflix deals in mind, things are starting to get a little bit shady, but even Tim Wu, the guy who coined the phrase "net neutrality," thinks it would be a mistake to over-regulate the internet in an attempt to keep things fair. This is not just a question of commercial fairness either. There are much bigger issues like free speech and the political process at play.

On the other hand, there's a solid argument to made about how trying to save the internet by banning fast lanes is like trying to fix a flat tire with duct tape. Even if the patch keeps the car on the road for a little while, it's still a temporary fix for a larger problem. The guys who run the internet's back bone all seem to agree that the solution is promoting competition between ISPs. After all, if a third of American households don't have a choice when it comes to their internet, of course the ISPs can do whatever they want behind the scenes. And when it's virtually impossible for small ISPs to face off against the big guys, we can't expect much progress.

Something needs to be done. While the consolidation of power among a small group of ISPs is a big problem, the smaller problems still need to be addressed. The FCC's new rules allow paid prioritization, and most net neutrality advocates would agree that this a bad idea. The second type of fast lanesthe peering connections and content delivery networksaren't necessarily a good idea. Banning them directly would bear bigger implications on the architecture of the internet.

But hey, since everybody's suddenly very interested in how the internet works, why not start that conversation? Why not start coming up with ways to increase competetion between ISPs? Why not give that little video start up a fair chance?

With nearly 700,000 rants already filed, the public comment period for the FCC proposed net neutrality rules is up at midnight on July 15. That means you only have a few hours left to submit your original thoughts. Reply comments*, however, will be accepted until September 10.

* As the name implies, reply comments are when members of the public can reply to each others' comments. Still, get your opinion heard while you can!

Netflix pays “tolls” to broadband providers, but it has made a big stink about doing so. Now the Internet Association, representing Netflix and other Web giants such as Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Amazon and others, has urged the FCC to adopt rules to keep the tolls from getting out of hand — and avoid the creation of fast lanes on the Internet.

The association submitted comments to the FCC today, ahead of tomorrow’s deadline for public comment on the agency’s planned net neutrality rules. Advocating for an open Internet, the Internet Association says it’s “urgent” that the FCC “adopt light-touch rules” to ensure consumers get equal, unfettered access to all Internet traffic. The group submission comes in the wake of some calls for Internet giants such as Google to do more to push for net neutrality. (Some of them have signed other letters to the FCC over the matter.)

“Segregation of the Internet into fast lanes and slow lanes will distort the market, discourage innovation and harm Internet users,” said Michael Beckerman, president and CEO of the Internet Association, in a press release.

As tech advances “have provided [ISPs] with an unprecedented ability to discriminate among sources and types of Internet traffic in real time and with little cost,” it’s important to draw up rules to stop them, the association said in its comments to the FCC. Among other things, the broadband providers should be required to be more transparent about how they handle traffic, TIA says.

But is trying to stop fast lanes practically moot? As we’ve mentioned, some reports have indicated that tech giants such as Google and Facebook already pay such tolls, although the companies haven’t responded to our requests to confirm this.

The Internet Association also says fixed and wireless broadband should be subject to the same rules; the FCC’s previous open Internet rules had treated them differently when it considered wireless connections as up-and-coming.

Larry Magid notes that ordinary netizens might want to join the hundreds of thousands of others who already have submitted their comments to the FCC. “Whatever side you’re on, this is a heated and important debate because it will affect the future of what has become the world’s most important communications and information network,” Magid writes. Comments on the initial comments will be taken until Sept. 10.

Proponents of net neutrality say the FCC’s proposed rules could mean the (oft-mentioned) end of the Internet as we know it; could hinder innovation; and give rise to discrimination and censorship.

The House today approved Blackburn's proposal by a vote of 223-200, according to The Hill. It would still need Senate approval to become law.

US Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) wants to make sure the Federal Communications Commission never interferes with "states' rights" to protect private Internet service providers from having to compete against municipal broadband networks.

Twenty states have passed laws making it difficult for cities and towns to offer their own broadband Internet services, and FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler has pledged to use his agency's authority to "preempt state laws that ban competition from community broadband."

He may get a chance to make good on that promise soon. EPB, a community-owned electric utility in Chattanooga, Tennessee said it is "considering filing a petition to the FCC" to overturn a state law that prevents it from offering Internet and video service outside its electric service area.

"There are vast areas of Tennessee, surrounding EPBs electric service territory, where citizens and businesses have little or no broadband Internet connectivity," EPB's announcement this month said. "For several years EPB has received regular requests to help some of these communities obtain critical broadband Internet infrastructure. However, since 1999, while state law has allowed EPB to provide phone services outside its electric service territory, it has prohibited EPB from offering Internet and video services to any areas outside its electric service area."

That's exactly what Blackburn wants to prevent. Yesterday, she proposed an amendment to a general government appropriations bill that would prohibit taxpayer funds from being used by the FCC to preempt state laws governing municipal broadband.

While Blackburn thinks the FCC shouldn't interfere with states' rights, she doesn't seem to be concerned about states interfering with municipalities' rights to offer their own broadband services. Here's what she said:

We don't need unelected federal agency bureaucrats in Washington telling our states what they can and can't do with respect to protecting their limited taxpayer dollars and private enterprises. As a former state senator from Tennessee, I strongly believe in states' rights. I found it deeply troubling that FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler has repeatedly stated that he intends to preempt states' rights when it comes to the role of state policy over municipal broadband.

...

States have spoken and said we should be careful and deliberate in how we allow public entry into our vibrant communications marketplace, a sector of our economy that invests tens of billions of dollars each year, accounts for tens off thousands of jobs, and serves millions of consumers.

She went on to say that "municipal broadband projects have had a mixed bag of results" including some successes "and also some spectacular failures that have left taxpayers on the hook."

For an example of a failure, she called out UTOPIA in Utah, where a bill to limit the network's growth was introduced in the state house this year. Blackburn did not mention EPB from her own state, which has provided much-needed competition to Comcast and AT&T and turned a profit.

Blackburn received $10,000 from the National Cable & Telecommunications Association this year and last year, according to OpenSecrets.org. She received $12,500 in contributions from Verizon, $10,000 from AT&T, $7,500 from Comcast, and $7,000 from representatives of Time Warner Cable. (These donations come from the companies' political action committees, employees, or owners.)

The billH.R. 5016, the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act of 2015was left as unfinished business yesterday. A roll call vote on Blackburn's amendment "was postponed, but it initially appeared to have enough votes for passage," according to the news site Broadcasting & Cable.

The National League of Cities, National Association of Counties, and National Association of Telecommunications Officers and Advisors yesterday sent a letter to Congress urging lawmakers to defeat Blackburn's amendment.

"tate laws that prohibit or restrict public and public/private broadband projects... harm both the public and private sectors, stifle economic growth, prevent the creation or retention of thousands of jobs, and hamper work force development," the letter said. "The private sector alone cannot enable the United States to take full advantage of the opportunities that advanced communications networks can create in virtually every area of life. As a result, federal, state, and local efforts are taking place across the Nation to deploy both private and public broadband infrastructure to stimulate and support economic development and job creation, especially in economically distressed areas. But such efforts are being thwarted in some areas by State laws that prohibit or restrict municipalities from working with private broadband providers, or developing themselves, if necessary, the advanced broadband infrastructure that will stimulate local businesses development, foster work force retraining, and boost employment in economically underachieving areas."

President Obama has come out in support of reclassifying internet service as a utility, a move that would allow the Federal Communications Commission to enforce more robust regulations and protect net neutrality. "To put these protections in place, I'm asking the FCC to reclassifying internet service under Title II of a law known as the Telecommunications Act," Obama says in a statement this morning. "In plain English, I'm asking [the FCC] to recognize that for most Americans, the internet has become an essential part of everyday communication and everyday life."

It's unclear so far exactly how the FCC will react to the president's splashy statements about net neutrality. Chairman Tom Wheeler and his cronies could simply decide to ignore Obama. But when the Commander-in-Chief says something like this, you'd hope the government agencies he's sort of* in charge of will listen:

More than any other invention of our time, the Internet has unlocked possibilities we could just barely imagine a generation ago. And here's a big reason we've seen such incredible growth and innovation: Most Internet providers have treated Internet traffic equally. That's a principle known as "net neutrality" and it says that an entrepreneur's fledgling company should have the same chance to succeed as established corporations, and that access to a high school student's blog shouldn't be unfairly slowed down to make way for advertisers with more money.

Inspirational, right? Obama's good at that. I said "sort of " above because, as Obama is careful to point out in his statement: "The FCC is an independent agency, and ultimately this decision is theirs alone." So they could just ignore him. But let's get into the details before we really consider that option.

The Plan

So Obama's asked the FCC to reclassify the internet as a public utility, like electricity or water. This means a lot of things. Suffice it to say that the internet gets a better square on the Monopoly board. Instead of just being a regular piece of real estate that can be bought or sold or modified or destroyed, the internet would enjoy a number of regulatory protections if it were classified under Title II of the Telecommunications Act.

The White House points out in a blog post about Obama's statement that the reclassification would represent a "basic acknowledgement of the services ISPs provide to American homes and businesses, and the straightforward obligations necessary to ensure the network works for everyonenot just one or two companies." That sounds about right. The internet was designed to be a free and open tool for communications.

So Obama's presenting a four point plan. You can read his full explanation of each point in the full statement below, but here are the important, pretty self-explanatory bullet points:

-No blocking.

-No throttling.

-Increased transparency.

-No paid prioritization.

No block and no throttling are obvious. Increased transparency is vague, but we'll come back to that in a second. Meanwhile, you've heard a lot about paid prioritization (fast lanes) from the big fight over the summer, when the FCC invited the public to comment on its pretty ****** rules. As we all know, lots of peopleover 4 million to be exactdid just that, breaking pretty much every record the FCC had for public involvement in its regulations. So the president agreeing with the public is a terrific thing! But, again, it does not mean that this solves the problem of protecting net neutrality for good.

What It Means

Now, let's get into the dirty details, because that's where this policy shift will either make or break the future of the internet. And there is most definitely a big asterisk on Obama's plan, an exception that some think spoils the whole thing.

The specific mandates that Obama lays out in his statement are exactly that: specific. It's important that he specifically forbids blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization, because pretty much everybody agrees that these are bad for the interneteverybody except, maybe, the ISPs like Verizon and Comcast who stand to profit from these practices. The FCC got into trouble with the American public for not specifically forbidding certain practices, namely paid prioritization.

The more general aspects of the Obama's plan raise a few questions. The president is very clear when he explains what being classified under the Title II of the Telecommunications Act of 1934 means:

For almost a century, our law has recognized that companies who connect you to the world have special obligations not to exploit the monopoly they enjoy over access in and out of your home or business. That is why a phone call from a customer of one phone company can reliably reach a customer of a different one, and why you will not be penalized solely for calling someone who is using another provider.

Almost a century! The Telecommunications Act is an old law, but it's a good one. Its provisions attempt to guarantee that consumers don't get screwed on services that are integral to daily life. In 1934, that meant telephones. Now, Obama's saying that it should also mean broadband internet. In his own words, this is just "common sense."

But there's a caveat herethat asterisk I mentioned at the top of this post. Right after his "common sense" remark, Obama says this:

So the time has come for the FCC to recognize that broadband service is of the same importance and must carry the same obligations as so many of the other vital services do. To do that, I believe the FCC should reclassify consumer broadband service under Title II of the Telecommunications Act while at the same time forbearing from rate regulation and other provisions less relevant to broadband services.

"Forbearing" is the key word there. The legal term is forbearance, which literally means "the action of refraining from exercising a legal right." In this context, forbearance means that some parts of the Telecommunications Act would not apply to the regulation of broadband internet, namely "rate regulation and other provisions less relevant to broadband services." That line reads like a hat tip to ISPs, a signal that the government is giving them a little bit of wiggle roomor a lot. It's kind of unclear.

It's long been argued that forbearance would be the key to preserving net neutrality. After all, until the government decides that it will become an ISP and provide Americans with internet access, broadband is a business. To preserve the free and open aspects of the internet, some compromises will have to be made for business interests.

At face value, the fact that Obama is offering ISPs forbearance on an undetermined number of aspects of Title II sounds like a trick. It's one of those devil-you-don't-know situations. Sure, he forbids bad things like fast lanes and throttling, but he's also saying that ISPs will get off the hook for an undisclosed number of regulations. Rate regulation is one that he does name. This means that regulators won't be able to tell ISPs how much they can charge customers. Obviously, ISPs like this idea. But what else won't regulators be able to do?

So keep an eye on this forbearance issue. It might become pretty problematic for the average consumer. Then again, it might be the trade-off we have to make so that the FCCand the companies that spend millions so that the agency respects their wishesactually approves an acceptable set of net neutrality rules.

Will It Work?

Once again, Obama's statement about net neutrality is great news. Great news always has its caveats, but look at it this way. About an hour after the White House released the statement, Tim Wu tweeted:

"The White House's announced Net Neutrality policy is 100% on target http://www.whitehouse.gov/net-neutrality "

Tim Wu is the Columbia Law School professor who invented the term "net neutrality." So if he likes Obama's policy, today is a terrific day for the internet. And it actually sounds like he loves the policy.

Keep this in mind when you wonder if it'll work. Will the FCC actually write new rules that conform to the president's wishes? We don't know. We can't know until they do or they don't!

Think of it this way, though. The FCC is not the American people's favorite agency right now. More than one individual commissioner has even admitted that the existing rules are bad. Meanwhile, the experts who understand how the internet works better than the FCC does say that Obama's plan is "100% on target." It's the FCC's job to listen to experts and do what's best for the American people. Now would be a good time for the FCC to do its job.

Read Obama's full statement below:

An open Internet is essential to the American economy, and increasingly to our very way of life. By lowering the cost of launching a new idea, igniting new political movements, and bringing communities closer together, it has been one of the most significant democratizing influences the world has ever known.

"Net neutrality" has been built into the fabric of the Internet since its creation but it is also a principle that we cannot take for granted. We cannot allow Internet service providers (ISPs) to restrict the best access or to pick winners and losers in the online marketplace for services and ideas. That is why today, I am asking the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to answer the call of almost 4 million public comments, and implement the strongest possible rules to protect net neutrality.

When I was a candidate for this office, I made clear my commitment to a free and open Internet, and my commitment remains as strong as ever. Four years ago, the FCC tried to implement rules that would protect net neutrality with little to no impact on the telecommunications companies that make important investments in our economy. After the rules were challenged, the court reviewing the rules agreed with the FCC that net neutrality was essential for preserving an environment that encourages new investment in the network, new online services and content, and everything else that makes up the Internet as we now know it. Unfortunately, the court ultimately struck down the rules not because it disagreed with the need to protect net neutrality, but because it believed the FCC had taken the wrong legal approach.

The FCC is an independent agency, and ultimately this decision is theirs alone. I believe the FCC should create a new set of rules protecting net neutrality and ensuring that neither the cable company nor the phone company will be able to act as a gatekeeper, restricting what you can do or see online. The rules I am asking for are simple, common-sense steps that reflect the Internet you and I use every day, and that some ISPs already observe. These bright-line rules include:

No blocking. If a consumer requests access to a website or service, and the content is legal, your ISP should not be permitted to block it. That way, every player not just those commercially affiliated with an ISP gets a fair shot at your business.

No throttling. Nor should ISPs be able to intentionally slow down some content or speed up others through a process often called "throttling" based on the type of service or your ISP's preferences.

Increased transparency. The connection between consumers and ISPs the so-called "last mile" is not the only place some sites might get special treatment. So, I am also asking the FCC to make full use of the transparency authorities the court recently upheld, and if necessary to apply net neutrality rules to points of interconnection between the ISP and the rest of the Internet.

No paid prioritization. Simply put: No service should be stuck in a "slow lane" because it does not pay a fee. That kind of gatekeeping would undermine the level playing field essential to the Internet's growth. So, as I have before, I am asking for an explicit ban on paid prioritization and any other restriction that has a similar effect.

If carefully designed, these rules should not create any undue burden for ISPs, and can have clear, monitored exceptions for reasonable network management and for specialized services such as dedicated, mission-critical networks serving a hospital. But combined, these rules mean everything for preserving the Internet's openness.

The rules also have to reflect the way people use the Internet today, which increasingly means on a mobile device. I believe the FCC should make these rules fully applicable to mobile broadband as well, while recognizing the special challenges that come with managing wireless networks.

To be current, these rules must also build on the lessons of the past. For almost a century, our law has recognized that companies who connect you to the world have special obligations not to exploit the monopoly they enjoy over access in and out of your home or business. That is why a phone call from a customer of one phone company can reliably reach a customer of a different one, and why you will not be penalized solely for calling someone who is using another provider. It is common sense that the same philosophy should guide any service that is based on the transmission of information whether a phone call, or a packet of data.

So the time has come for the FCC to recognize that broadband service is of the same importance and must carry the same obligations as so many of the other vital services do. To do that, I believe the FCC should reclassify consumer broadband service under Title II of the Telecommunications Act while at the same time forbearing from rate regulation and other provisions less relevant to broadband services. This is a basic acknowledgment of the services ISPs provide to American homes and businesses, and the straightforward obligations necessary to ensure the network works for everyone not just one or two companies.

Investment in wired and wireless networks has supported jobs and made America the center of a vibrant ecosystem of digital devices, apps, and platforms that fuel growth and expand opportunity. Importantly, network investment remained strong under the previous net neutrality regime, before it was struck down by the court; in fact, the court agreed that protecting net neutrality helps foster more investment and innovation. If the FCC appropriately forbears from the Title II regulations that are not needed to implement the principles above principles that most ISPs have followed for years it will help ensure new rules are consistent with incentives for further investment in the infrastructure of the Internet.

The Internet has been one of the greatest gifts our economy and our society has ever known. The FCC was chartered to promote competition, innovation, and investment in our networks. In service of that mission, there is no higher calling than protecting an open, accessible, and free Internet. I thank the Commissioners for having served this cause with distinction and integrity, and I respectfully ask them to adopt the policies I have outlined here, to preserve this technology's promise for today, and future generations to come.

Congresswoman defends states rights to protect ISPs from muni competition

http://arstechnica.com/business/201...rights-to-protect-isps-from-muni-competition/

Sneaky bastards got that one in under most of our noses. Screw states rights when it screws the people they should be fighting for

Beat me to it, was just about to post that. Great news indeed

EDIT: This will go into more detail about what it all means

So we aren't out of the woods yet

"Net Neutrality" is Obamacare for the Internet; the Internet should not operate at the speed of government.

Ever wonder why big cable companies can do whatever they want? It's partly because the FCC keeps its revolving door spinning. But it's also worth knowing that the politicians in charge of regulating the telecom industry not only receive campaign funds from them; some of them directly invest in companies like AT&T and Comcast.

Put more bluntly: Some members of Congress profit from the same companies they're supposed to police. Four members of the House Energy Subcommittee on Communications and Technologythat's the committee that's specifically in charge of regulating the telecom industry, including the internethold investments in AT&T, Comcast, and Verizon. When these companies make big profits, these Congressmen share in them.

Financial disclosures reveal that four members (including the chairman) of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce and one member of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation hold personal investments in AT&T, Comcast, and/or Verizon. Some of these men also serve on subcommittees that are specifically in charge of legislating the internet and telecommunications industry. And some of these investments are significant.

The following details come straight from the lawmakers' 2013 Personal Financial Disclosure statements. (Data from 2014 is not yet available.)

Hon. Fred Upton (R-MI)

Chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce and ex-officio member of the Subcommittee on Communications and Technology

AT&T* (investment amount: $15,001 - $50,000; reported income from investment: $0)

Comcast* (investment amount: $1,001 - $15,000; reported income from investment: $0)

Verizon (investment amount: $1,001 - $15,000; reported income from investment: $1 - $200)

* Rep. Upton's wife invests $15,001 to $50,000 in AT&T and receives $1,001 to $2,500 in annual income from that investment. She also invests $1,001 - $15,000 in Comcast and receives $1 to $200 in annual income from that investment.

Hon. John Dingell (D-MI)

Member of House Energy and Commerce Committee and all six subcommittees including the Subcommittee on Communications and Technology

AT&T (investment amount: $1,001 - $15,000; reported income from investment: $0)

Comcast (investment amount: $15,001 - $50,000; reported income from investment: $201 - $1,000)

Leonard Lance (R-NJ)

Member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Subcommittee on Communications and Technology

AT&T (investment amount: $15,001 - $50,000; reported income from investment: $2,501 - $5,000)

Comcast (investment amount: $1,001 - $15,000; reported income from investment: $1 - $200)

Verizon (investment amount: $15,001 - $50,000; reported income from investment: $201 - $1,000)

* All of Rep. Lance's investments in these companies come from his stake in the estate of Mae Anderson. It's plausible that he did not actively invest in these companies.

Frank Pallone (D-NJ)

Senior member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and member of the Subcommittee on Communications and Technology

Verizon* (Investment amount: it's complicated; reported income from investment: it's complicated)

* Rep. Pallone's wife invests $15,001 to $50,000 in Verizon and receives $201 to $1,000 in annual income from that investment. Three of his children invest $1,001 to $15,001 in Verizon, and two of them receive $1 to $200 in annual income from those investments. The third receives $0.

The legality of these investments is a contentious issue. Lawmakers investing in anything is always a bit dicey, since they often have access to information that the public does not. In 2012, Congress passed the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act to address those potential conflicts. This increased transparency by adding new disclosure requirements for lawmakers and some members of the executive branch.

However, for the most part, it's not illegal at all for lawmakers to invest in the companies that they regulate. "In sum, there are no restrictions on any kind of investments," Meredith McGhee, Policy Director at the Campaign Legal Center, told us. "Members in the House (and Senate) are not required to divest. To recuse or abstain from voting, they have to have a 'direct personal or pecuniary interest in the event of such question.' That is interpreted to mean when legislation affects a 'class' of people and not a few individuals."

The issue is especially pressing now. Despit President Obama's recent statements about net neutrality, the FCC won't be addressing net neutrality until next year, the agency's spokeswomen said recently. This could complicate the debate quite a bit. A few weeks of FCC stalling gives others in Washingtonnamely lobbyists andmore time to get involved. President Obama's net neutrality plan lit many fires under many asses. And now, Congress is warming up to the idea of intervening in the FCC's process.

It's possible that some of these lawmakers have shed all or part of their investments in big cable, but it doesn't seem likely. We contacted each of the congressmen and asked them to clarify whether they kept their investments from 2013 in their portfolio for 2014. No one provided an answer either way in time for this story.

It's literally malware

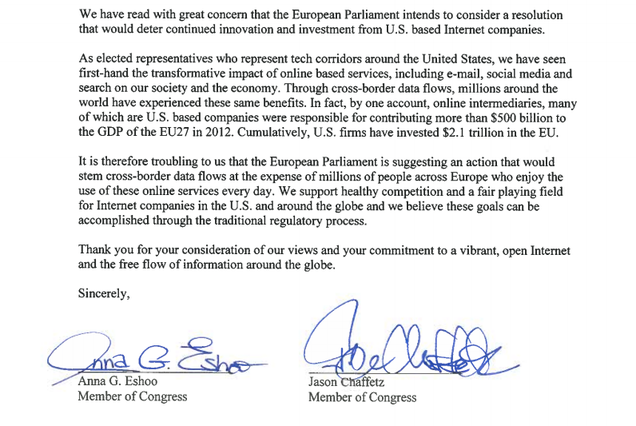

Yesterday twelve U.S. Congressmen signed, sealed, and delivered a letter (embedded below) to members of the European Parliament lobbying their counterparts to leave Google alone. According to the Financial Times, at least three letters from American legislators were sent as part of a "rare and concerted public intervention" on Google's behalf.

The letter obtained by Valleywag argued that by taking it easy on "U.S. based Internet companies" (code word for Google), the EU could promote "a vibrant, open Internet and the free flow of information around the globe." Funny because promoting a vibrant and open Internet was kinda what the EU was trying to do.

Tomorrow members of the European Parliament will vote on whether Google's search engine, which has more than 90 percent of the market in much of Europe, should be split from Google's other money-making services for abusing its near monopoly as the people's portal.

Another amusing aspect of this transcontinental lobbying effort? Signatories like Representative Darrell Issa have argued against net neutrality right here on American soil. Issa and "social media ace" Jared Polis, who also signed the letter below, have intervened on Google's behalf before, back when the Federal Trade Commission was considering an antitrust lawsuit against the tech corporation in 2012.

They waged an epistolary campaign then too. According to The Hill, Issa (a Republican) argued that the FTC would "step beyond its legal power to regulate anti-competitive business practices" and Polis (a Democrat) went further, threatening the FTC that "a lawsuit against Google would be disastrous and could prompt Congress to limit the agency's authority."

The letter signed by Issa and Polis also included Anna Eschoo, Jason Chaffetz, Zoe Lofgren, Kevin Yoder, Mike Honda, Blake Farenthold, Tony Cardenas, Peter Roskam, Eric Swalwell, and George Holding. A source mentioned that Jerry Brown is playing pen pal as well.

The Financial Times reports that Ron Wyden, Orrin Hatch, Dave Camo, Sander Levin, and Bob Goodlatte were also part of the letter writing campaign.

Capitol Hill hit back at EU lawmakers on Tuesday for politicising an antitrust investigation into Google, as tensions rose ahead of a European parliamentary vote calling for the possible break-up the technology group.

In a rare and concerted public intervention on Google's regulatory travails in Europe, senior US politicians expressed "alarm" over a draft resolution advocating the potential unbundling of search from Google's other commercial internet services.

Although the letter below doesn't mention Google outright, there's a clear link back. The upcoming vote, which is expected to pass, is European Union's latest attempt to yell "antitrust" in Google's ear. But it's a non-binding resolutionmore of a signal than anything else. And the only entity that would be bothered enough to send in the calvary is good ole GOOG.

WASHINGTON—Newly fortified Republicans in Congress are considering a number of ways to stymie the Obama administration’s planned regulations on broadband Internet providers in 2015, making Capitol Hill a new front in the fight over “net neutrality.”

Concern about the rules is playing into Republican efforts to rein in what they say is regulatory overreach by the Federal Communications Commission.

Dissension over the Internet rules is so rancorous that it could end up impeding progress on technology policy areas where there is potential for agreement, such as cybersecurity and the allocation of wireless spectrum, according to telecom lobbyists and congressional aides.

The FCC spent most of 2014 drafting the new rules for how broadband Internet providers manage their networks, and it plans to vote on a final rule in February. Shortly after the midterm elections, President Barack Obama called on the FCC to impose the strongest possible rules on providers by classifying broadband as a utility, which would make it subject to much greater regulation. The rules are designed to protect net neutrality—the principle that all Internet traffic should be treated equally.

Many conservatives and the broadband industry say utility-like regulation is a step too far, arguing it will stifle innovation in the industry. That view is held by some pivotal players in the new Congress, such as John Thune (R., S.D.), the incoming chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee.

Right now, a 30-year-old engineer is on trial for founding and operating an enormous online black marketthe Amazon of drugs. The outcome of his trial could change the way we use the internet.

In 2011, it was possible to buy pretty much any illegal drug you desired on a single websiteThe Silk Road. Today (right now!), the United States is trying to put away Ross Ulbricht, the man they say ran the operation. This is more than just the trial of an alleged drug dealer: The outcome of this case will shape how the public looks at emerging technologies like bitcoin, online privacy, and the role of the federal government in policing the web. Motherboard put it well:

The case will address many issues that have never before been argued in a US court, and many believe it will set precedents for privacy and the extent to which the government holds people responsible for content on their sites and servers.

As the internet uneasily settles into its new role as as a global commerce hub and powerful driver of immense economies, governments have become increasingly aggressive in ensuring their interests are representedeven, and maybe especially, when it means betraying ideals of anonymity and freedom held dearly by the web's early adopters.

If Ulbrichta name to a facegoes down for the Silk Roada drug market for the facelessit'll discourage a lot of would-be imitators who want a narcotics free-for-all, and represent the most high-profile way the internet's promise of true anonymity has been undermined by the state. But if "Dread Pirate Roberts" eludes the FBI once again, it'll make the darker corners of the internet a whole lot more confident to do what they please in the shadows.

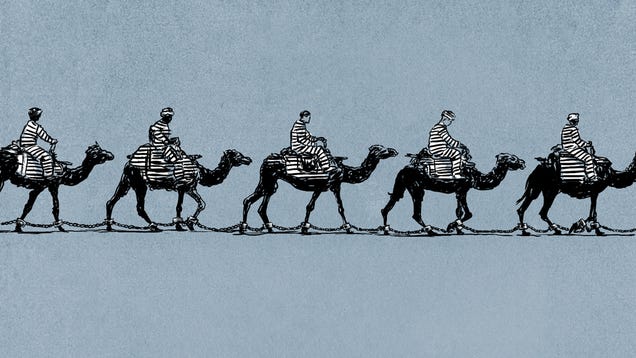

Silk Road

Before Gawker's Adrian Chen revealed it to the world, hardly anyone had ever heard of the Silk Road, and it flourished. You could browse the site pretty much like you'd browse any other e-commerce destinationso long as you were accessing it via an anonymous connectionbuying as much or as little of your preferred narcotic from a wide variety of pseudonymous vendors. It wasn't the prettiest website (screenshot below), but it was functional and straightforward.

What allowed the Silk Road to work was anonymity. It could be accessed only through Tor, a piece of software that allows encrypted, anonymous access to hidden websites around the worldperfect for both a foreign dissident and a drug dealer.

Silk Road was also quite possibly what popularized bitcoin, so perfectly suited for illicit transactions.

"Dread Pirate Roberts": Silk Road's Mastermind

Because of the collective anonymity of the site's participants, it was impossible to tell who was in charge. The site's administrator went by "Dread Pirate Roberts." Feds say the man behind "Dread Pirate Roberts" is Ross Ulbricht.

Details gleaned after his arrest show a surprisingly ordinary man; certainly not someone who screams INTERNATIONAL DRUG MASTERMIND:

Browsing Ulbricht's social media accounts show a pretty normal, nerdy guy. Ulbricht graduated from the University of Texas in 2006 with a degree in Physics and went to the Pennsylvania State University for grad school, where he studied engineering and wrote a master's thesis on "Growth of EuO Thin Films by Molecular Beam Epitaxy." According to property records, he owned a home in State College, PA, which he sold in 2010 for $187,0000. Curiously, the indictment misidentifies his grad school as the University of Pennsylvania.

He's got a Facebook page full of beer pong pics and, of course, was a vocal supporter of Ron Paul, donating $200 to his campaign in 2007. "He doesn't compromise his integrity as a politician and he fights quite diligently to restore the principles that our country was founded on," Ulbricht told the Penn State student newspaper in 2008.

Nonetheless, police accuse him of making an enormous amount of money on the Silk Road:

According to the indictment, Silk Road was bigger than anyone had suspected: It boasted over $1.6 billion in sales from 2011-2013, which resulted in $80 million in commissions. (Researchers had previously estimated that Silk Road was doing about $22 million in total sales per year.) According to the indictment, which claims that FBI agents obtained a mirror of the server that housed Silk Road's business from law enforcement in an unidentified foreign country, Ulbricht "alone has controlled the massive profits generated from the operation of the business." He used some of the profits to pay a team of administrators as much as $2,000 a week each. And yet, he only paid $1,000 a month in rent for his San Francisco apartment, according to the indictment.

The Investigation

According to a detailed Wired account of the investigation, a DHS informant in Baltimore told the feds about Silk Road. Cops managed to identify site moderators and administrators, and started making arrests to get closer to Dread Pirate Roberts.

How did they pull that off? As Wired puts it, the "FBI's Story of Finding Silk Road's Server Sounds a Lot Like Hacking":http://www.wired.com/2014/09/the-fbi-finally-says-how-it-legally-pinpointed-silk-roads-server/

As bureau agent Christopher Tarbell describes it, he and another agent discovered the Silk Road's IP address in June of 2013. According to Tarbell's somewhat cryptic account, the two agents entered "miscellaneous" data into its login page and found that its CAPTCHAthe garbled collection of letters and numbers used to filter out spam botswas loading from an address not connected to any Tor "node," the computers that bounce data through the anonymity software's network to hide its source. Instead, they say that a software misconfiguration meant the CAPTCHA data was coming directly from a data center in Iceland, the true location of the server hosting the Silk Road.

Is Ross Ulbricht "Dread Pirate Roberts"?

Ulbricht doesn't deny creating the Silk Roadjust using it to sell drugs. On the first day of Ulbricht's trial, Motherboard reports his attorney did not deny that his client founded the site:

However, while Ulbricht's attorney Joshua Dratel admitted for the first time in court Tuesday that Ulbricht did create Silk Road as an "economic experiment," he claims thedefendant passed the site to other administrators when running it became "too stressful" after just a few months in 2011.

But feds have a lot of evidence linking Ulbricht to the Dread Pirate Roberts drug baron identity.

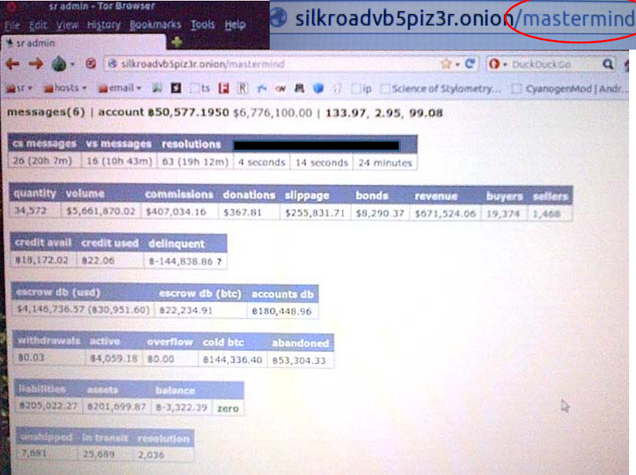

Over at the Daily Dot, you can view a rough outline of what the FBI is trotting out against Ulbricht in court. Vast chat transcripts, screenshots from Ulbricht's laptop, and internal Silk Road communiques are at the ready. Photos like this one, which law enforcement says was on Ulbricht's laptop screen (the "mastermind" controls for Silk Road) when he was arrested in San Francisco:

Or this one (his strangely ample collection of fake IDs)

could go a long way in convincing a jury that he was indeed responsible for a criminal conspiracy to traffic narcotics around the globe and throughout the United States.

But it's important to note that Ulbricht's criminal defense doesn't hinge on distancing himself completely from the Silk Roadsimply showing that some other person (or persons) could have been operating the Dread Pirate Roberts persona, acting as the drug market's chief administrator and leader. Proving that a single person is the sole operator of a pseudonymous internet account based on pseudonymous software channels will not be easy for the feds.

The Trial

Bitcoin is still so new, complex, and untested that it's tough to explain what it is to a layman, let alone prove that it was instrumental in Dread Pirate Roberts' global drug ring. To how many people could you stop on the sidewalk and easily explain the functionality of Tor? Even if the prosecution can provide a convincing argument that Dread Pirate Roberts and Ross Ulbricht are one in the same, can they prove beyond a reasonable doubt that this in itself was a crime, and not just an internet screen name?

But the verdict could change the way we use the internetand the way the government regards it, too. The Silk Road trial is a simple drug trafficking case in some ways, but it's also going to make us confront the difficult reality that just because certain online activities have managed to skirt or challenge established law so far doesn't mean that the internet will forever remain a Wild West. As Woodrow Hartzog, an associate professor of law at Samford University and scholar at the Stanford's Center for Internet and Society, put it:

Online black markets are likely to continue to be created and shut down. Yet this trial has also reminded us of the limits of technology. When the Internet was in its infancy, many thought online activity was also beyond the reach of the law. We've seen time and time again this is just not true. Bitcoin is a very powerful and interesting technology, but it is important not to overestimate innovation. It's equally important not to underestimate how our offline actions can make us vulnerable online. Perhaps the most significant impact of this trial is to serve as a reminder not to be overly confident in online anonymity, particularly in the face of substantial resources.

Australian security consultant and fervent Silk Road analyst Nik Cubrilovic told me he thinks the trial has already altered the net, verdict aside:

Consequences of the Ulbricht trial are already being felt. They are good or bad depending on your viewpoint. First thing is that many vendors, users and market administrators who are less confident in their ability to shield themselves from federal law enforcement have given up. The administrators of Agora [another darknet market] are considered the most technically and security adept and they spent the 2 weeks [after November '14 darknet raids by police] in a complete state of panic.

Even having hidden markets like Silk Road raidedlet alone prosecutedhas been enough to push copycats deeper underground, says Cubrilovic:

Gone are the days where starting a market was as simple as Googling 'how to setup a tor hidden service' and then installing some off-the-shelf market software. Those guys have all been arrested, and anybody with that lower level of skill has been scared away.

The End of Anonymous Browsing?

Most importantly, the FBI will be free to use the same, possibly illegal methods it employed to take down the Silk Road on future targets:

The FBI has also done a good job of keeping their methods and techniques close to their chest. There has been a level of cooperation here from the justice system and the presiding judgewhat usually happens is that to convict someone or to grant them a fair trial the methods used in the arrest would have to be scrutinized. The pre-trial in Ross' case concluded that the FBI didn't have to reveal their server uncovery method - and even if it was hacking it would still be ok. This means law enforcement are free to apply the same methods again, they didn't have to 'burn' their techniques.

This would be a huge win for any government apparatus that wants to decrypt the channels we've been assuming are safeit wasn't so long ago that Edward Snowden relied on Tor to protect his whistleblowing activity.

Security expert and CloudFlare researcher Marc Rogers sees two courses depending on the jury's decision. If the FBI manages to convict Ulbricht, Rogers "suspect that the primary long term effect of this is that we will see further prosecutions of hidden Tor services."

This means further attempts to de-cloak services which violate US law and that may lead to collateral damage as not all hidden services are illegal drug markets. Undermining one category of hidden services potentially undermines them all.

A not guilty verdict, however, "carries the most risk."

Prosecutors and law enforcement are under immense pressure to "do something" about the underground drug markets. Failure to successful prosecute the single largest and longest running of these will almost certainly add fuel to the call for more and stronger laws to arm the justice department.

It was only a matter of weeks before Congress capitalized on the Sony hack to give the odious CISPA legislation another go. If the FBI can't pry the darknet's drug baron out of hiding, there's every reason to expect it'll just ask for scarier tools.

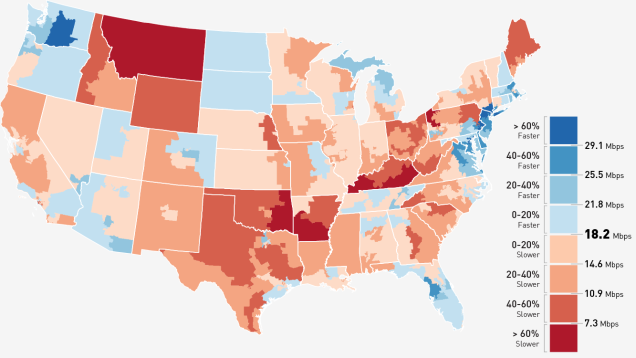

In the wake of the ongoing net neutrality argument, another equally important squabble between regulators and telecoms companies has been overlooked. The FCC is trying to redefine 'broadband' as "internet which is actually fast enough to use", and telecoms companies don't like that one little bit.

According to current FCC policy, 'broadband' means 4Mbps down/1Mbps up. That's been the definition since 2010, when it was upgraded from a (hilariously slow) 200Kbps. However, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler recently outlined a plan to update that definition, to 25Mbps down/3 up. It's a position supported by a number of companies, including Netflix; but unsurprisingly, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association (NCTA) is dead against the plan.

As arbitrary as the 25/3 numbers sound, they're not picked totally out of thin air: they're based on a clause in the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which states that broadband must "enable users to originate and receive high-quality voice, data, graphics, and video telecommunications using any technology".

Based on that criteria, broadband should be fairly easy to define. Netflix publishes a handy little chart of how fast your internet has to be in order to stream video from its servers. To get any kind of buffer-free service, they recommend a 1.5Mbps connection, with 5Mbps recommended for HD, and 25 for 4K content.

Going by those numbers, saying that 25Mbps is the minimum standard for broadband seems a little excessive. 4K content is a rare beast on the internet, and the necessary equipment for watching it a 4K TV is rarer still (although, give it five years and we'll see how things change).

But an alternative argument for a 25Mbps standard, put forward by policy group Public Knowledge, is that a single internet connection is commonly shared between several individuals. If, say, three members of a five-person household are streaming Netflix at the same time, you'd need a minimum of 15Mbps in order for everything to work seamlessly and that's assuming that the Wi-Fi network isn't causing any slowdown.

In a FCC filing on Thursday, the NCTA claimed that no-one needs internet that fast, saying that 'hypotheticals' like people sharing one internet connection "dramatically exaggerate the amount of bandwidth needed by the typical broadband user", and that "a relatively small percentage of consumers who have access to speeds of 25 Mbps/3 Mbps actually choose to purchase service at those speeds". Of course, that has nothing at all to do with the non-existent competition and subsequent price gouging on high-speed plans, compared to low speed internet. Nothing at all.

Why does all this matter? Well, you see, the FCC is required to "encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability [read: broadband] to all Americans". So if it doesn't think that enough households have broadband, it can use a selection of tools to 'encourage' competition tools that scare companies like Comcast or TWC.

So it's clear why the telecoms companies want to keep the definition of broadband down: a lower threshold for broadband keeps regulators off their backs, and allows them to perpetutate the (very valuable) oligopoly that exists in the high-end broadband market.

And, in turn, the position of companies like Netflix and Google, who are advocating for faster broadband speeds, should be equally clear. Faster internet means a better experience for consumers, which means more paying customers for Netflix, and more eyeballs on videos for YouTube.

From an individual's perspective, there aren't really any downsides to the bar for 'broadband' being moved higher. If the FCC gets its wish, and overnight 25/3 becomes the minimum standard for broadband, the only negative effects will be for telecoms companies that sell internet packages. They'll be shamed for not offering broadband to wide swathes of America; but more importantly, an 'entry level' broadband package will be something you might want to own, rather than a low-price face-saving tool designed to make telcos look good.